The Marmottan is off the beaten path, but the high discovery quotient here makes the ride out to the western city limits well worth the trip. With the exception of Monet’s late waterlilies, you are not likely to see things that seem already familiar—no art book déjà vu.

With a knowledgeable Paris Muse specialist in Impressionist art with you, the Marmottan’s offers a rare opportunity to learn about the movement in an in-depth way. But the museum is much more than Impressionism.

What gives the collections here their under-stated charm is an ability to spark appreciation for lesser-known artists (the Empire portraitist Louis Boilly, late Impressionists Armand Guillaumin, or the under-rated Berthe Morisot), or for lesser-known works by household names (early caricatures by Monet from the 1850s, a small, stunning portrait of Morisot by Manet).

The Marmottan is actually three museums in one: 1) First Empire art, furniture and objets d’art; 2) medieval sculpture and manuscripts; 3) Monet, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Most people clearly come for No. 3, but end up being quite surprised and pleased by the visual treats of courses No. 1 and 2.

The Marmottan is actually three museums in one: 1) First Empire art, furniture and objets d’art; 2) medieval sculpture and manuscripts; 3) Monet, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Most people clearly come for No. 3, but end up being quite surprised and pleased by the visual treats of courses No. 1 and 2.

This eclectic menu is the result of individual donations, and each grouping still speaks to the personality of a collector. The first was art historian and Boilly specialist Paul Marmottan, who donated his home as a kind of First Empire museum to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in the 1930s. Marmottan had an unerring eye for the sleek geometry of early 19th-century Empire furniture, displayed here in a suite of elegant rooms on the ground floor. Look for exotic touches like the gilded sphinxes that reflect a Napoleonic craze for all things Egyptian. The highlights of this collection are a gallery of portraits by Boilly, a Sèvres geographical clock, and a spectacular rock crystal chandelier in the shape of a bird cage.

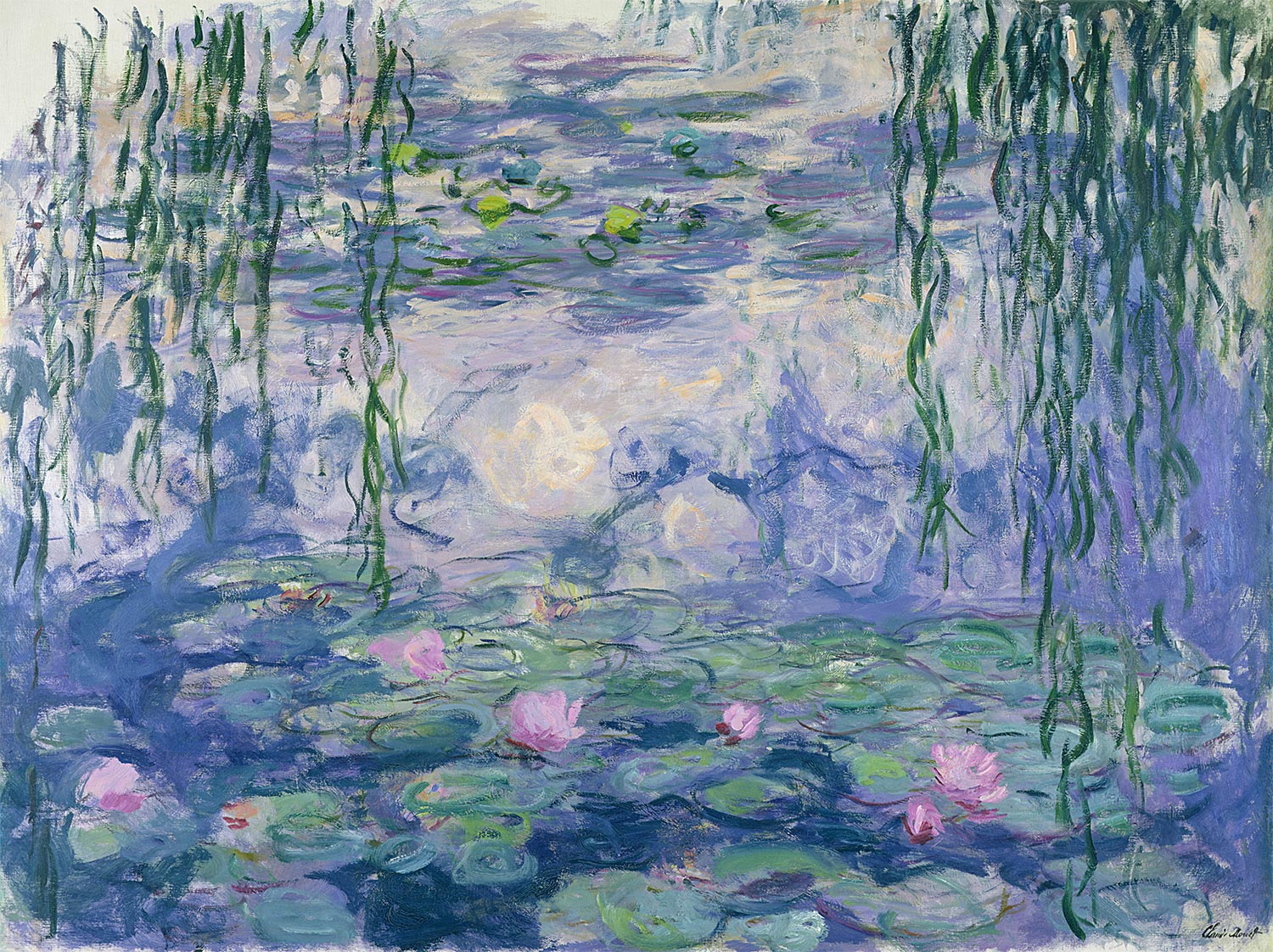

Marmottan’s museum did not become a Monet mecca until 30 years later, when the painter’s son Michel donated his own inheritance of over 150 works and personal affects (sketchbooks, press clippings, family photos, his father’s palette), creating the world’s largest museum collection of Monets. If your vision of this Impressionist painter conjures only tame, pretty walks in the countryside, the basement galleries of the Marmottan will be quite an eye-opener. Monet’s late textural work still has that fresh, painted-yesterday feel, and rivals the best of later 20th-century “pure painting” abstraction.

Many visitors immediately gravitate to Monet’s early “Impression, Sunrise” (1873), the painting that earned the Impressionist movement its (originally derogatory) moniker. In the chapel-like circular gallery displaying the majestic Giverny Nymphéas (1916-1920), you can see the end result of Monet’s early fascination with capturing light effects on water. In these works, you are not looking at a landscape so much as plunged directly into one.

Daniel Wildenstein’s illuminated manuscript collection on the first floor is not to be missed. This medieval section of the Marmottan will soon be enhanced with 13th-century stained glass from the cathedral at Soissons, scheduled for a March installation.