In this installment of Talking With Muses, we sit down with our guide Barbara Montefalcone to learn how poetry and visual art go hand in hand.

Barbara (above) has been leading tours for Paris Muse since 2009 and is currently a Professor at the Paris College of Art and a consultant for the Terra Foundation for American Art.

When not leading tours, you are a Professor at the Paris College of Art (PCA) and also Chair of their Liberal Studies Department. How does being a docent for Paris Muse inform your work in the classroom, and vice versa?

All my different professional activities have something in common: they all demand engaging with people. Dialogue is something from which you constantly learn, and I find giving tours for Paris Muse helps me be a better teacher. Explaining the history of art to very young visitors in our family tours is particularly useful and enriching. Teachers are most effective when they can keep material simple and clear, and convey passion. In both my tours and my classroom, I love focusing on details that allow people to enjoy a piece of art.

Can you tell us a bit about the curriculum and the students you have at the Paris College of Art?

The Liberal Studies curriculum at the Paris College of Art provides students with a grounding in general humanities – history, philosophy, languages and literature – as well as social sciences and sciences. This is combined with a wide selection of elective courses including theater, cinema and film studies, gender studies, music, dance and much more. And we’re not just diverse in terms of area of study. Our students and faculty come from all over the world – from more than 50 countries in fact – and this makes PCA a vibrant and unique place. It reminds of my own experience when I left my native Italy to study French and American literature and British theater in Warwick, England. My classmates came from such different backgrounds, and we learned to adapt to new systems and methods and come together to share knowledge. I believe this sort of diversity is a source of enrichment for everyone.

Literature and Art are often treated as separate fields, but your research explores how much they have in common. Can you tell us more about this?

For my Ph.D. I merged my love of literature and art by studying the relationship between painting and poetry. My dissertation looked at the work of Robert Creeley, an American poet who created collaborative books with famous painters. I was fortunate to be able to work with him at Brown University before he passed away in 2005. As a professor, I continue to not just study the intersection of literature and visual arts but also promote engagement. In 2011, with the support of a Terra Foundation for American Art grant, I organized a symposium that explores the connections between the two fields. American and European poets and painters were invited to participate. My latest book, The Art of Collaboration: Poets, Artists, Books, is a volume from this symposium which I co-edited. I titled my essay in this volume “Poetry is a Team Sport,” which is actually a quote from Robert Creeley who said:”Poetry is a team sport, you can’t play it all by yourself.” Creeley stressed the importance, for both the poet and the sportsman, of sharing a determined space and time, and of being part of a collaborative act whose results are both personal and common. This is an idea that I particularly like.

A great example you give of this in practice is the “artist book.” What is an artist book? What makes it different than an illustrated book?

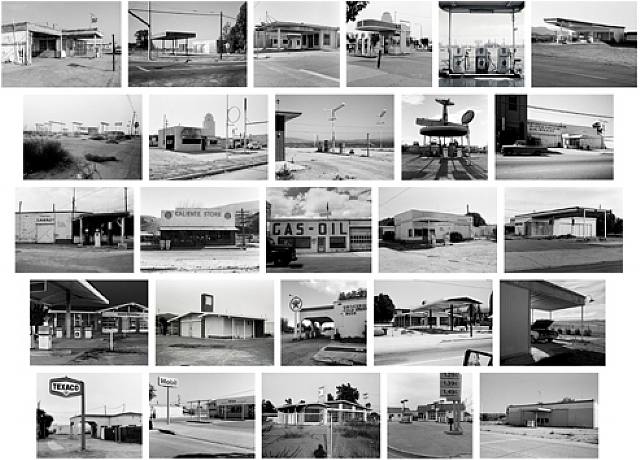

Simply put, an artist book is a book made by an artist. It is artwork in the form of a book. The first artist book was Ed Ruscha’s self-published photography book called Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963). While artist books are often collectors’ items today, they were originally a way for artists to distribute their work outside of galleries and make art accessible. They were self-published, made of cheap materials, and often free. Collaborative books, another variation on this genre, are another example of how the crossover between art and writing can take the form of a book. In these cases, poets and writers reach out to artists who then illustrate their book. Their arts inform each other. This is different from an illustrated book in which the publisher reaches out to an illustrator.

How did you become so interested in this particular form of expression?

I first fell in love with books when I was a child. My parents own a wonderful library of both literature and art books, and when I was young I spent whole afternoons looking at pictures and reading poems. Then, as an undergraduate in Italy, I took a 20th century art history course and a modern literature course in the same semester. It was a revelation to me how many connections could be drawn between the two. From that moment on I decided to explore the relationship between modern and contemporary poetry and painting. That brought me to study first illustrated books, then collaborative books and then, finally, artist books. So the serious interest really came from my university years, but I believe that there was already something there from my past that sparked my love of illustrated books. For instance Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry has been one of my favorites since my mother first gave it to me when I was a teenager.

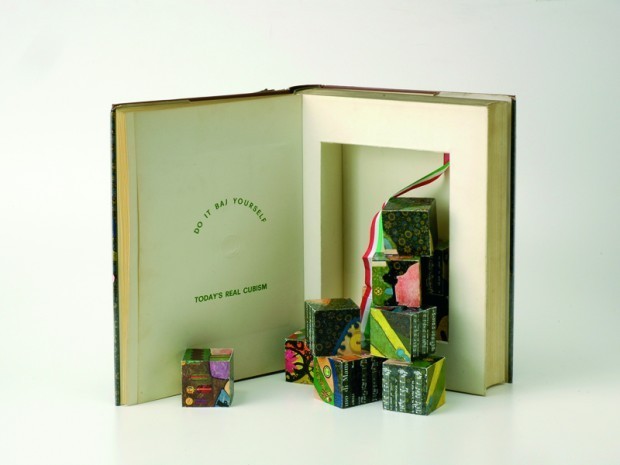

What are your favorite artist books? And where can we find them?

That’s a difficult question! The research library of the Centre Pompidou has an incredible collection, including Ed Ruscha’s photography books and another I particularly cherish by the Italian artist Enrico Baj and Italian poet Edoardo Sanguineti. It is an “object book” (a book which does not look like a book, but more like a piece of sculpture) entitled The Biggest Art Book in the World (1968). It is made of a series of cardboard cubes that the reader can mix up and play with in order to create an image. It’s a playful activity that the authors define as “today’s real cubism.” It’s unique, beautiful, and full of irony – the perfect ingredients for a good book!