Longtime Paris Muse educator Dr. Katie Hornstein talks to us about the joys of teaching in Paris museums.

We caught Dr. Katie Hornstein between tours and archive visits to find out which museums are not to be missed in Paris, which Louvre galleries she loves to share with visitors the most, and why lions make for a compelling research topic. Katie divides her time between Paris and New Hampshire, where she is a Professor of Art History at Dartmouth College. She just finished her first book on how war and battle were represented in paintings and photographs in 19th-century France.

How did you get started leading tours for Paris Muse?

I started working for Paris Muse almost ten years ago in 2007, when I was still a graduate student writing my dissertation. At the time, giving tours gave me a much-needed break from research and writing. I quickly found that introducing art to clients in museums gave me another outlet for approaching art history: it was less academic and more personal.

What do you enjoy most about leading tours for Paris Muse?

I love learning with my clients as we talk about art. I also love having a job that lets me spend time in museums. There really could not be anything better. When leading tours, I strive to convert people into art lovers: not just in terms of appreciating beauty or technique, but also understanding how complex a work of art can be.

Is there a particular piece of art in Paris that you especially enjoy sharing with visitors?

I always get a thrill out of taking visitors to the Grands Formats rooms in the Louvre. The enormous paintings were called grandes machines for a reason: their scale immediately arrests any viewer and compels attention. There is no way to understand these paintings without first experiencing their immense scale.

How has your experience as a Paris Muse docent shaped your career as a professor?

Engaging with Paris Muse visitors in front of works of art was ideal training for working with students in a classroom. The hundreds of hours that I’ve spent in the Louvre, the Musée d’Orsay, and the Rodin museum have shaped the way that I teach art history in the classroom. I can speak with authority about the way that works of art look because I have spent so much time in front of them. This is a gift for an art history professor (and hopefully for my students!). I would actually go so far as to say that working for Paris Muse did more than anything else in terms of teaching me how to teach.

Which are your favorite off-the-beaten-path museums in Paris?

My favorite small museum is the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (Museum of Hunting and Nature): it’s probably the most creatively-curated museum in Paris and there’s a surprise behind every corner. It’s also great for kids because there are all of these drawers that they can open and explore. There’s also some very creative taxidermy!

I also love the Musée des Arts et Métiers (Museum of Arts and Crafts) because it houses so much 19th-century technology, which is one of the things that I’m fascinated by; I think that walking through the museum’s galleries gets us as close as possible to the feeling of what exhibitions of new inventions must have looked like just after the French Revolution.

Can you tell us more about your most recent research project?

I just finished my first book that is tentatively entitled Picturing War in France, 1792-1856. It looks at war pictures from the outbreak of the French Revolutionary wars up through the Crimean War, which was the first war to be photographed on a relatively wide scale and covered in the newly-illustrated mass press. I’m interested in the ways that war became accessible to a broader public after the French Revolution as an image: the French public flocked to see large-scale battle paintings, but also paid good money (about the price of a movie ticket today) to see 360-degree monumental painted battle panoramas. This research topic has allowed me to think about the politics of being a consumer of war images and it gives me a way to think about the emergence of mass culture at the dawn of the industrial age.

A hearty congratulations on your upcoming book! I hear you already have a second project underway too?

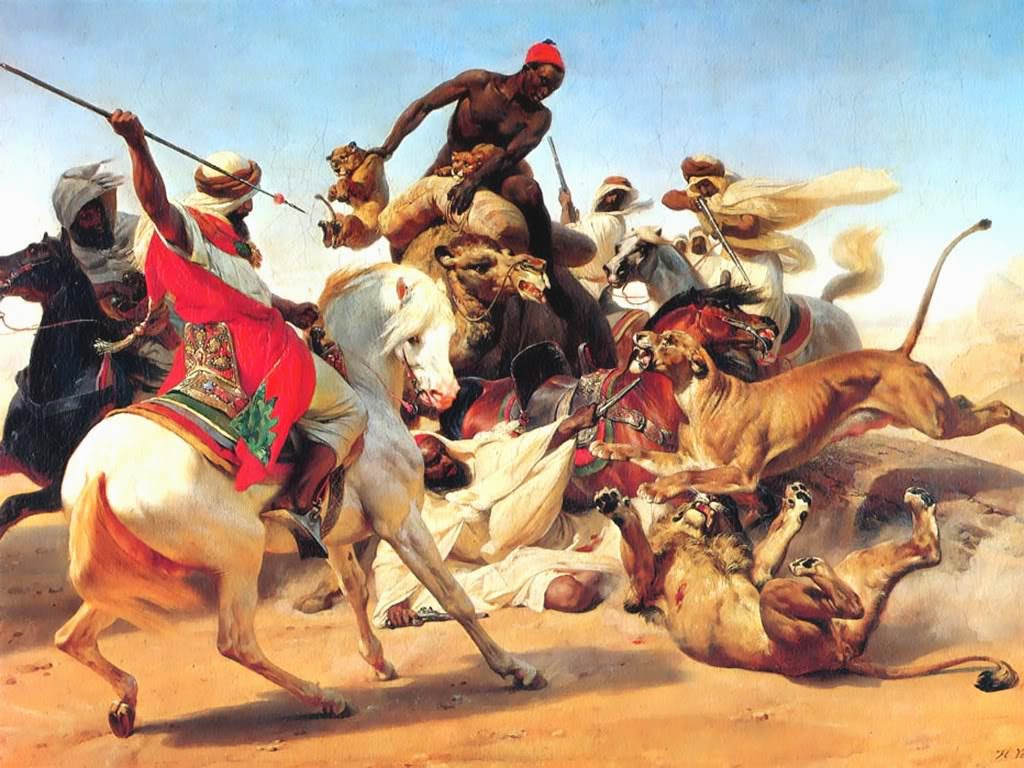

My new research project is a little different! I’m still interested in the emergence of mass culture, but I’m looking at it through another lens: lions! It’s tentatively entitled: Beasts within: Leonine Encounters in Post-Revolutionary France. I’m interested in live lions in zoos and circuses as well as works of art that depicted lions. I’m also thinking about French colonial history here, especially in Algeria post 1830, when France became the center of the live lion trade because of its foothold in Algeria. This is when you get an artist like Delacroix making dozens of lion paintings and the sculptor Barye, whose Lion Attacking a Serpent is on display in the Cour Puget at the Louvre.