Our guides pick their favorites. Have you seen all twelve?

The Lacemaker by Johannes Vermeer, 1669-1670

The Lacemaker by Johannes Vermeer, 1669-1670

Karen: Our attention is fixed firmly on the lacemaker, all aglow in a warm light. The palette is soft and the background plain so there is nothing to distract us. We catch her silent and unawares. Completely engrossed in her work, she does not pose for us, she does not even notice us. Vermeer is so good at giving us these quite, contemplative moments.

The Coronation of Emperor Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David, 1806-07

Beate: This is one of those paintings that just can’t leave you indifferent, and not just because of the impressive scale. Sumptuous, glamorous, dazzling, The Coronation is a superb piece of propaganda,effortlessly legitimizing Napoleon’s firm grip on imperial power. It’s great fun as well, with its world of heroes and social climbers, ambition and hypocrisy, vanity and betrayal, splendor and meanness. In short, a great human comedy. Nobody sums it up as well as Napoleon himself: “This is not a painting, one walks into this picture.” I could not agree more!

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault, 1818 – 1819

Emma: In 1810 a French Naval ship ran aground off the coast of Senegal forcing 150 sailors onto a raft for 13 days. Only 10 survived. To capture the tragedy, Géricault interviewed survivors and even visited the morgue so that he could render the cadavers aboard his raft with unforgiving accuracy. It all sounds pretty grim, doesn’t it? But you cannot help but see the immense beauty this painting holds: the dance between light and shadow, the immaculate brushwork, the luscious locks and rippling torsos of his heroic sailors. Tragedy never looked so good.

Melissa: Smoke, chaos, death, and above it all, a woman. She is no mere mortal, but a virtue, “Liberty,” leading the way during the 1830 Revolution. The colors of the French flag are scattered throughout the scene to masterful effect, while the pyramid of bodies draws the eye up to Liberty herself. A call to revolt, this painting was not to be taken lightly. After 1831, the new government hid the painting away for decades. But Liberty would eventually reemerge as Marianne, the Republic’s national symbol.

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci, 1503-19

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci, 1503-19

Raquel: By the time we get to Leonardo’s famous portrait on our Paris Muse Clues: A Louvre Family Tour, my young detectives are pointing out the artist’s innovative use of landscape and perspective, light and dark, as well as his signature shading and shadowing effect, called sfumato. I ask my fellow detectives whether she deserves so much attention. More likely than not, the response is an overwhelming yes!

See these paintings and more on our wide selection of Louvre tours.

Ploughing in the Nivernais by Rosa Bonheur, 1849

Giulia: A hymn to healthy, pristine rural life, Rosa Bonheur captures the magnificent realism of the oxen and makes the clods of earth look so real. Commissioned to create this work in 1849 by the French State, Rosa was a very strong personality and a highly successful painter, unusual for a woman in those times. I feel connected to this painting because the lovely Chateau de By, where the artist spent the last 40 years of her life, is only yards away from my house.

Olympia by Édouard Manet, 1863

Charlotte W.: She may be a courtesan, but Olympia definitely has a look that says “Don’t waste my time!” I always found this femme fatale attitude empowering. We, as viewers, get an insight on this cheeky scene – the bouquet brought in by the maid tells us that her next client is probably waiting in the antechamber. Meanwhile, Olympia’s black cat, with its arched back, seems to be telling us to back off and mind our own business, making the experience even more exciting: the painting offers a private world of its own.

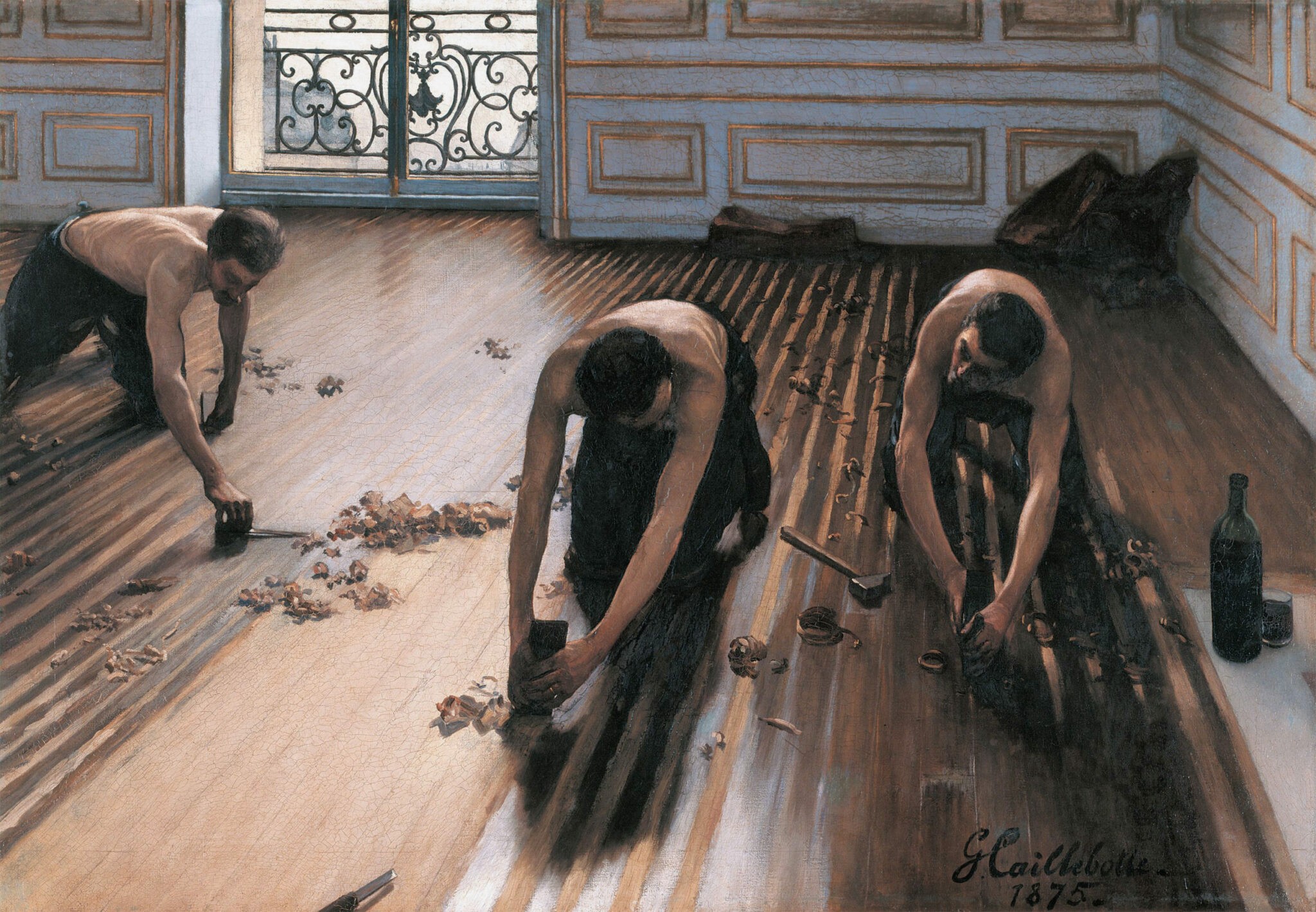

The Floor Scrapers by Gustave Caillebotte, 1875

Stephanie: Three laborers are stripping the wooden floor of a Parisian apartment, which may seem like a strange choice for a painting. But by creating a scene of manual work, imbued with graceful monumentalism, Caillebotte captures the beauty of the everyday. He also successfully accomplishes what Charles Baudelaire described in his call for modern art to depict the “heroism of modern life.”

Learn more about these paintings on our Age of the Impressionists at the Orsay tour.

The Water Lilies Cycle by Claude Monet, 1920-1926

Karine: The open, light-filled space of the two Monet galleries at the Orangerie takes you away, not only to Monet’s virtual garden, but to an infinite sense of peace. As a long-time Parisienne, I’ve been to the Orangerie museum several times to enjoy Monet’s Water Lilies, to get away from the city’s hustle and bustle. But now I finally grasp the extent of the modernity of Monet’s daring project, as an Impressionist leader who influenced the bold experiments of mid-20th-century American Abstract Expressionist painters.

Odalisque with Gray Trousers by Henri Matisse, 1926-1927

Ellen: Matisse may be serving up some outdated French fantasies about the exotic harem, the female quarters of an Islamic home where the kept odalisque dwelled. But he’s also deeply engaged with Islamic design ideas, borrowing from North African objects like the textiles and brasero (room heater) at the models’ feet, for example. Look at how complex all those competing patterns are, creating multiple layers of dynamic space. People come to the Orangerie just for Monet, but then end up discovering the modern collection downstairs, with dazzling visual jewels like this one.

See these works and others on our Monet and More at the Orangerie tour.

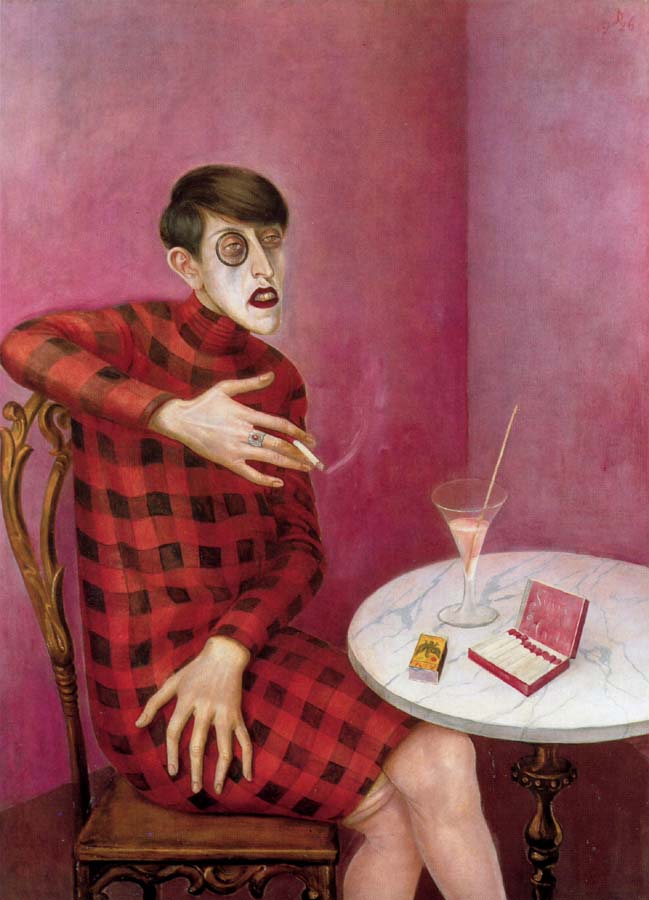

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden by Otto Dix, 1926

Yonit: At a time when many artists were embracing abstract art, the German painter Otto Dix developed a highly realistic style of painting. The details and accessories immediately draw one’s attention: from Sylvia von Harden’s monocle to her stockings, the long cocktail straw, and unique ring on her finger. I am always fascinated by her subversive androgynous appearance, extenuated by her dark red lipstick and close-cropped haircut. It may sound odd, but I would have loved to borrow her geometric patterned dress!

Untitled (Black, Red over Black on Red) by Mark Rothko, 1964

Inge: Standing before a Rothko painting is like a religious experience. The artist himself recommended that people stand very close, as little as 18 inches away, to his canvases, to be enveloped by his broad color fields. Do it long enough, and you can feel the floating blocks of color positively vibrating, as if they were pushing outwards or rushing inwards in all directions, leaving the viewer with nothing but the naked truth. Don’t be fooled by the lack of figures in Rothko’s art; in his own words, “There is no such thing as good art about nothing.”

Explore these works and others on our Masterpieces of Modern Art at the Pompidou Center.