Take your time to see and enjoy each meaningful detail. That’s the idea behind our Hidden Masterpieces tour of the Louvre.

Here are a few of our favorite paintings from the tour. Each one has an entire story in its details:

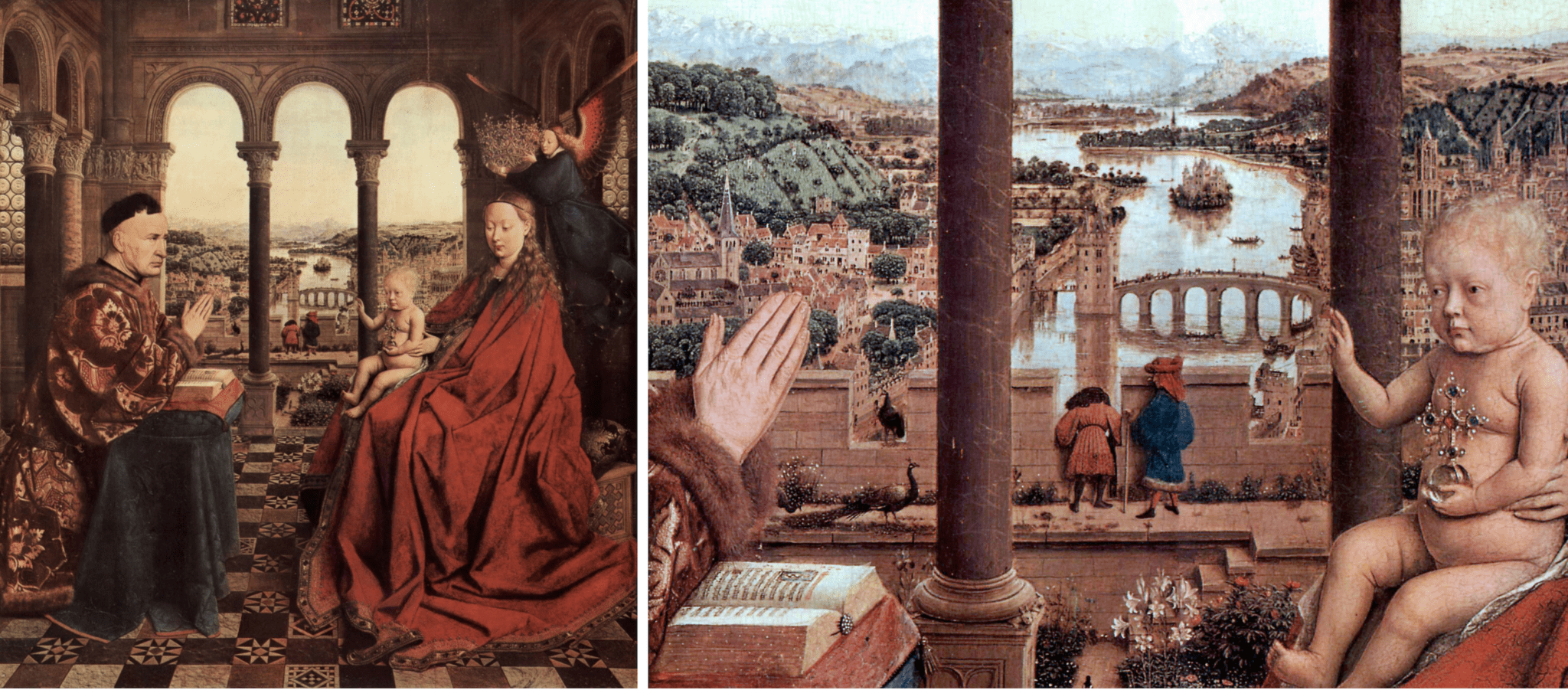

Chancellor Rolin Madonna by Jan van Eyck

At first glance, it looks like there are three figures in this exquisite altarpiece made in the early 15th century for the private chapel of a high-ranking court dignitary, Chancellor Rolin: the Chancellor himself, the Virgin Mary, and the Christ Child. Four if you count the angel. But look again. Out on the balcony in the distance, two small figures peer out over the landscape through a wall. Who are they?

Theories abound: Jan van Eyck himself and his assistant? The artist was known to include himself in his works. Allegories for vice and virtue? Or a clever way to hide a vanishing point, if indeed van Eyck used one? One thing is for sure: they, like us, are looking. Lest our eye be tempted to stop and linger over the lavishly-rendered details in the foreground – the softness of the chancellor’s fur collar and cuffs, the deep folds in Mary’s lush velvet cloak, or the light masterfully reflecting off the bottle-bottom window to the left – they invite us to come closer. Follow their lead, and a whole other world, as wondrous as the first, opens up. Such is the reward for those who are never not looking.

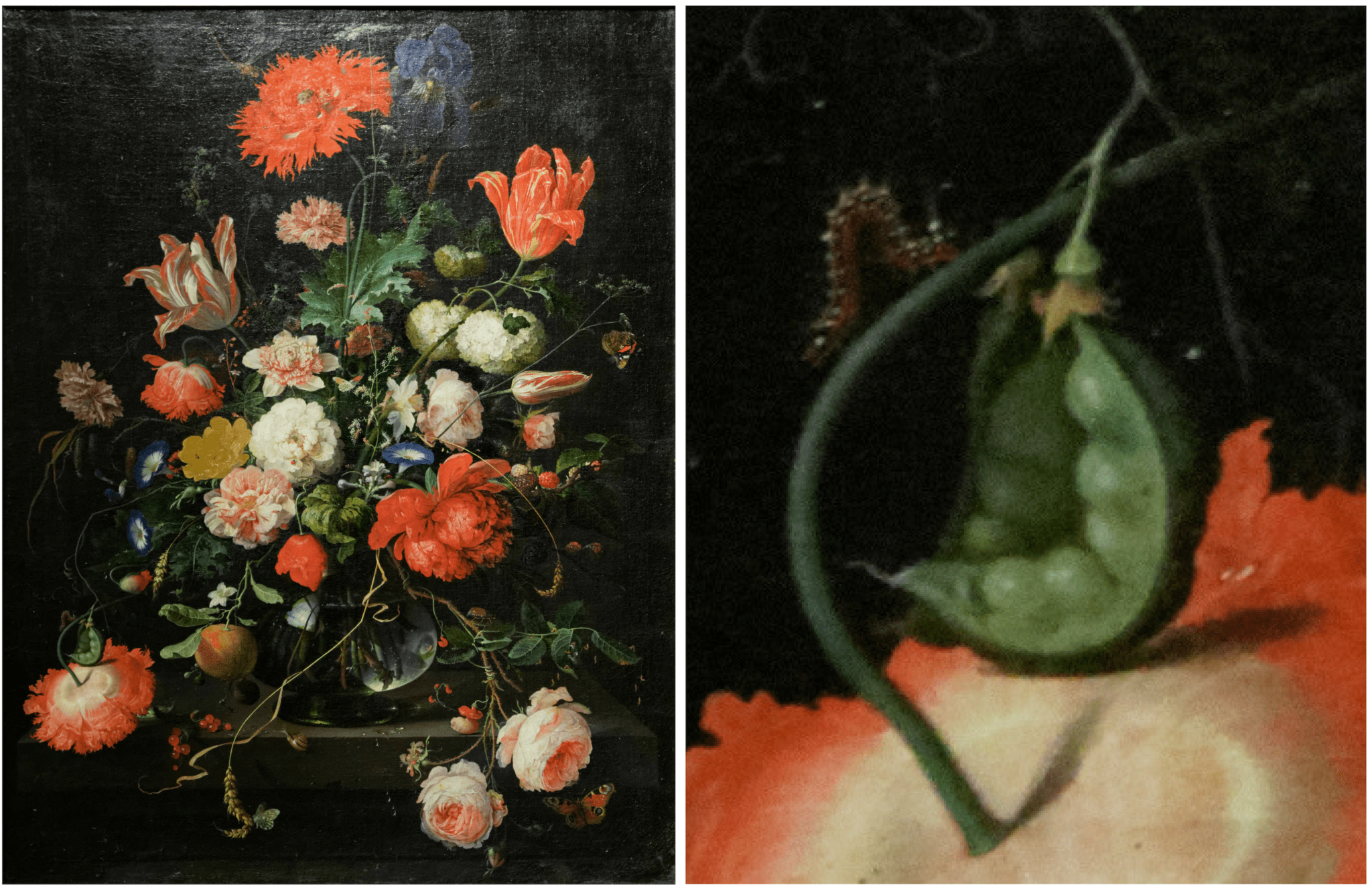

The Beautiful Vase by Abraham Mignon

Sumptuous floral arrangements are a staple of Dutch painting of the Golden Age (17th century). In this one by Abraham Mignon, bright red peonies as large as your fist burst open, standing out against a black background. Cabbage roses too heavy for their slender stems bow their petal-laden heads. The lush petals of striped tulips seem almost velvety. And slowly, they appear: a whole cast of critters buzzing and crawling all over Mignon’s beautiful vase. Up top, a dragonfly is about to alight on a bloom; several butterflies flicker about; a small snail clings to the edge of the stone shelf.

Come a little closer. Do you see it? A worm inching up the stem of a peony on the lower left. The bouquet may be bristling with life, but the inevitable forces of death and decay have already started to set in. The painting is a reminder that the things of this world are fleeting. Dutch still lifes allow – indeed encourage – us to revel in beauty, but never for very long. The more we look, the more we see that even those beautiful blooms are past their prime. Luckily, this is a painted – not a real – bouquet, so the pleasure, while still fleeting, lasts for as long as we look.

The Bad Company by Jan Steen

If paintings made noise, this would be a loud one. We’re in a tavern and clearly this has been a rowdy evening: a man passed out cold from too much drink and revelry is now being ripped off by a group of wily women as the band plays on in the back. The sundry items strewn across the tavern floor include discarded oyster shells, scattered playing cards, shards of glass, and a broken clay pipe. Jan Steen is so famous for these scenes of disarray that there is an expression in Dutch for messy homes: a “Jan Steen household”.

The clay pipe, broken into three pieces, lies just beneath the drunkard’s limp hand, the strong verticals of his legs and arm leading your eye easily to it. This detail has personal meaning to me, because on a visit once to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Dutch galleries with my mother, she excitedly pointed out that she and her siblings growing up in Dutch-speaking Belgium used just that kind of clay pipe for blowing bubbles! They show up everywhere in Dutch paintings and are a true reflection of everyday life in the Low Countries. But you needn’t have a Dutch mom to appreciate the deeper significance. What is more fragile or fleeting than a bubble? Is Steen commenting on how frail the human condition is? One thing is for sure: this fellow’s bubble has burst.

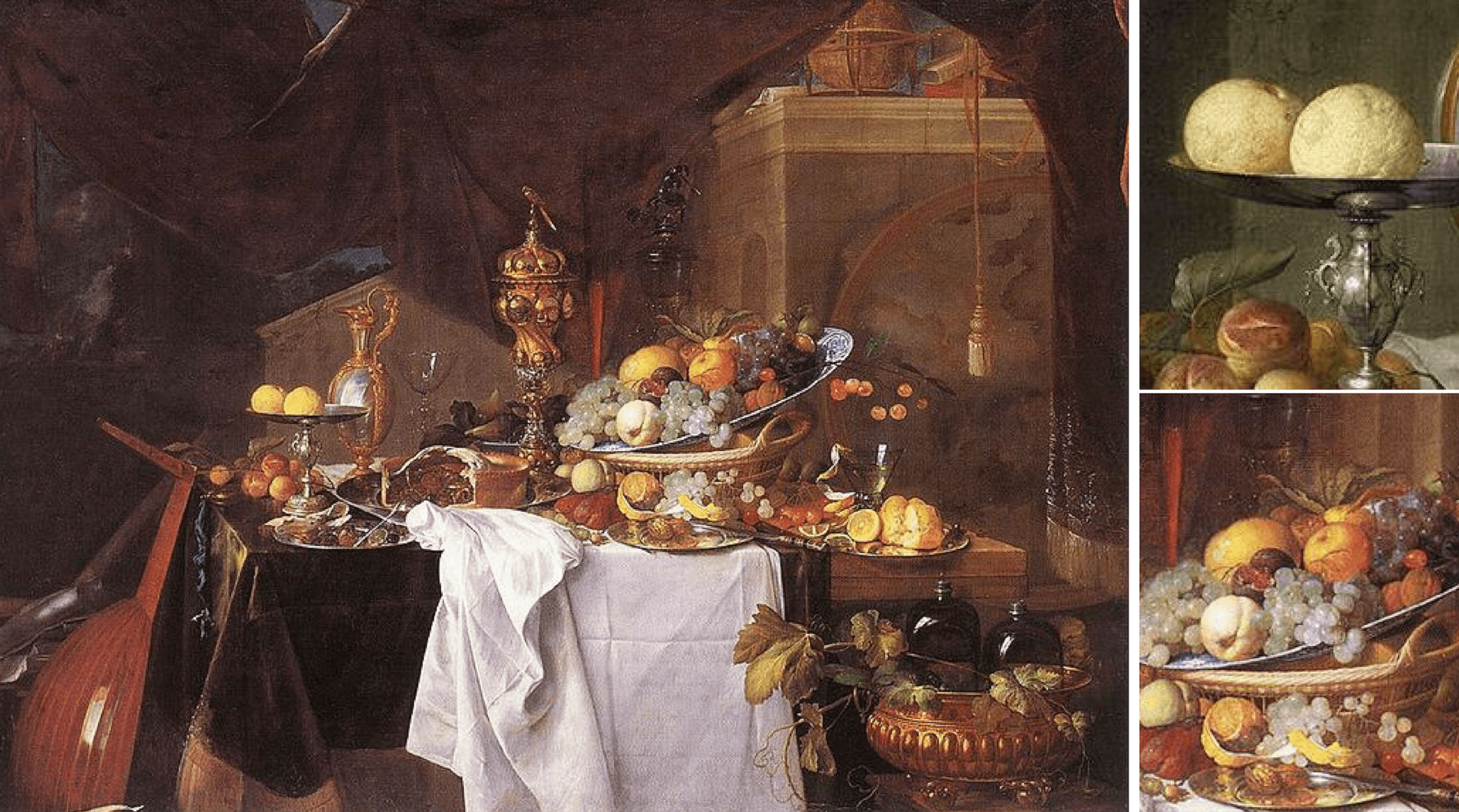

A Table of Desserts by Jan De Heem

Along with floral arrangements, tables laden with delicious foods and precious objects often take center stage in still life from the north. Here, a sumptuous feast is laid out before us, engaging all of our senses: the sheer delight of looking at such an artful arrangement; the imagined aroma of stewed plums wafting from the open tourte; the music made by a lute on the left; the soft bloom on the skin of grapes. If your mouth is not watering yet, the sight of lemons will surely do the trick. There are two to the left perched on a footed plate, and two partially-peeled to the right, one of the rinds spiralling up and catching onto the rim of a glass. Lemons are literally a sour fruit, reminding us that even the finest things in life lose their appeal if we misuse – or overuse – them. The lemon is a call to constraint for the viewer, and a touchstone of talent for the artist. It requires great skill to render the nubby peel, spongy pith and glistening flesh convincingly.

In fact, all this close looking inspired me to create my very own real-life Dutch still life. Here it is below, complete with a typical 17th- century drinking glass!