An exhibition celebrates the creative renewal Van Gogh found in the very last months of his troubled life.

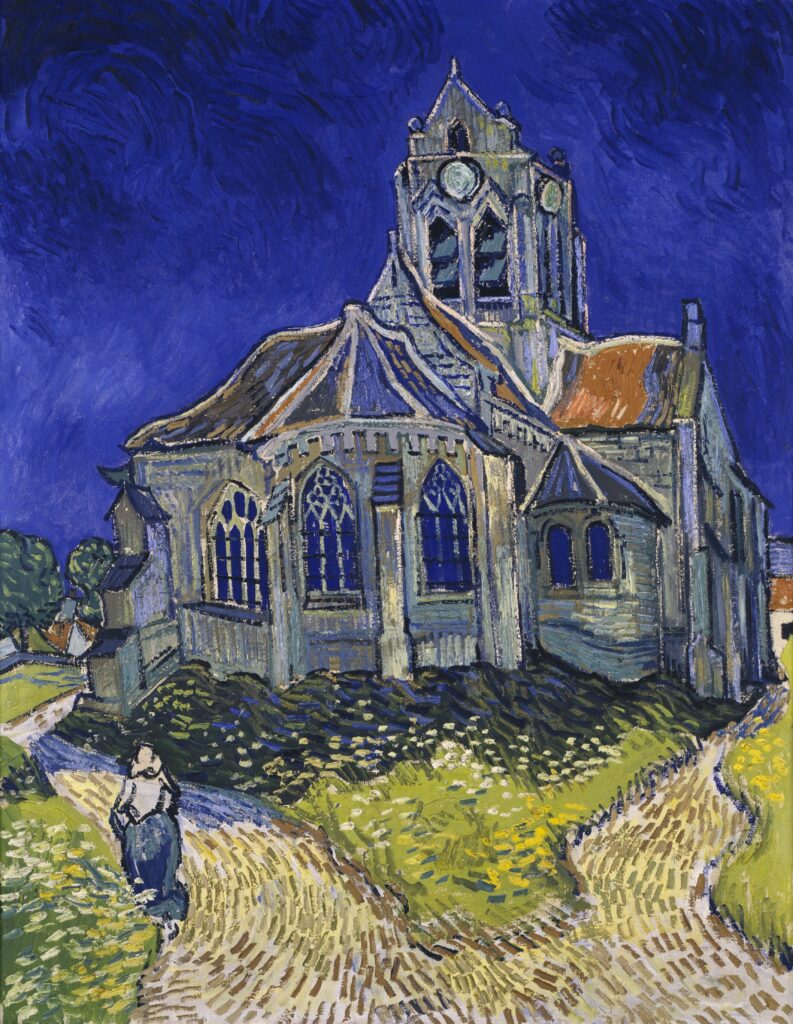

Visitors to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris flock to gaze at Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night, one of the museum’s most iconic works. Through February 4, 2024, there’s even more reason for fans of the famed Dutch artist to head to the Orsay: Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise, The Final Months.

Paris Muse guide and museum curator Marta Volga de Minteguiaga-Guezala is leading private tours of this acclaimed exhibition, the first ever to focus on the last two months of van Gogh’s life. (Reservations by request at info@parismuse.com). We asked Marta to tell us what makes this exhibition so unique.

Q: The concept for this exhibition is very moving—looking at just the last two months of van Gogh’s life in Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890. Could you tell us more about that time in his life?

A: It’s the first-ever exhibition dedicated to the last two months of his life, when van Gogh was just 37 years old. He had already been suffering from serious psychiatric problems, but he found a sort of serenity in Auvers-sur-Oise. The village was near Paris, so he could be close to his brother Théo. He also went there in search of new creative energy. You can see how he found it in his paintings, which are even stronger, more powerfully expressive than before. Even though van Gogh was suffering in these final months, and eventually died of a self-inflicted wound in 1890, he was able to produce some of his greatest masterpieces. I agree, that’s a moving accomplishment.

Q: It’s been said that van Gogh also chose Auvers-sur-Oise because of Dr. Gachet, who was known for his treatment of melancholia. I’m thinking of one of the Orsay’s many van Gogh paintings, his Portrait of Doctor Gachet. Can you tell us the story between these two men, and how it relates to the portrait?

A: When van Gogh returned to Paris after his stay in Arles and the asylum of Saint-Rémy in southern France, he looked for a place to paint, away from the agitation of the city. His friend, the painter Camille Pissarro knew Paul Gachet in Auvers and recommended him to Théo, Vincent’s brother. In addition to his homeopathic practice, Dr. Gachet was an enthusiastic supporter of the Impressionists and an amateur painter himself, which made him an ideal doctor for van Gogh. The relationship between the two promptly became a real friendship. Vincent even wrote to Théo that Gachet was like a new brother to him. In the Orsay’s famous portrait of Gachet, the doctor holds a foxglove plant, the source of the digitalis that he may have treated van Gogh with. So it’s a tribute to their connection through both art and healing.

Q: More than any other artist, van Gogh is the archetype for the link between creative genius and mental illness. And yet, he was incredibly productive. I think his life challenges some of our ideas about anxiety and depression. What do you think about the issue of mental health as it relates to his work? Does it risk overshadowing it?

A: In the final months he was often producing a painting a day! So not at all the stereotypical view of a depressed person who does nothing. For van Gogh, painting was the strongest—and perhaps his only—weapon to fight his mental illness. It was a perpetual internal struggle against the number one enemy of his art. Of course you can’t avoid this aspect of Van Gogh if you want to deeply understand his work. At the same time, we shouldn’t reduce his work to his illness either, looking at paintings as if they are literal illustrations of his struggles with sanity. You can see the intensity of the aesthetic emotion without knowing anything about his mental health struggles. When looking at a Van Gogh, we should use the same observational and analytic tools that we do for any other artist. How else can you appreciate his creative process? That’s what my tour focuses on too: looking closely at the work, specifically his bold color combinations and innovative brush strokes which forever enlarged the expressive range of art.

Q: What’s your favorite work in the current exhibition?

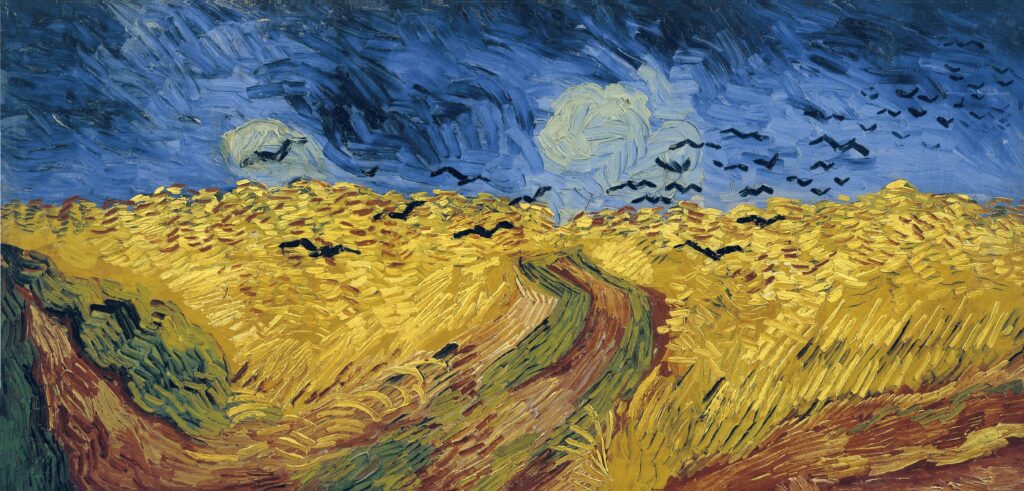

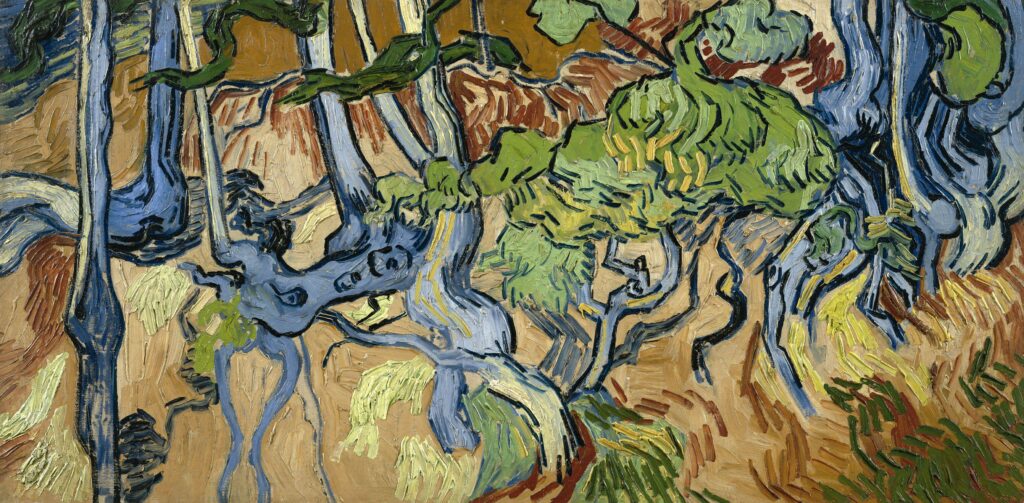

A: It is too difficult to choose only one! In just two months, he made 74 paintings and 33 drawings, after all! I love the chestnut blossoms, a painting he made after a branch he took from Gachet’s garden. It is both sweet and strong at the same time. I also love Wheatfield with Crows, which for a long time was thought to be his very last painting. We now know, however, that it was one of the unusual double-square canvases he used for his final landscapes: Tree Roots and Trunks (see image above), on loan to the Orsay from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. You can see that it’s a closeup image of energetic roots and trunks, but the subject almost doesn’t matter, because this incredible painting is nearly abstract, a swirling interaction of colors.