Paris Muse docents describe some of their favorite details from the tours they offer. Get a feeling for what’s in store for you when you reserve with us.

Auguste Renoir’s “Bal du Moulin de la Galette” (1876)

From “The Ag e of Impressionists” at the Musée d’Orsay:

e of Impressionists” at the Musée d’Orsay:

Renoir’s painting depicts the Moulin de la Galette, an outdoor guinguette, or dancehall in Montmartre. With its open fields and windmills, Montmartre was a popular get-away for Parisians, right at the doorstep of the hustle and bustle of the city. Renoir captures how the Sunday sun shines on the revelers enjoying the dancehall’s open courtyard. The warmth of the crowd is reinforced by the warmth of this light. Splotches of flickering sunlight dance all over this canvas, infusing the scene with energy.

As an Impressionist, Renoir was fascinated by how light effects our perception of colors. Instead of using black or gray tones to create shadow, he used striking color contrasts. Look, for example, at the strobe effect of the pink against the blue, in the dress worn by the woman in front. He combines these colors to create an impression of the fabric’s sheen and texture. As a result, you get a sense of the dress as a lively, moving thing. It is difficult now to imagine how radical this painting truly was, when Renoir exhibited it for the first time at the third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877. While it looks effortless—as if Renoir dashed it off with a few spontaneous strokes— it was in fact a carefully planned composition that took him all of the summer of 1876 to paint. Renoir remains one of the most beloved of the Impressionist painters because he makes us feel like we are on holiday, when our own labors are temporarily forgotten for something that feels effortless, too.

Learn about this painting on our Age of the Impressionist tour at the Orsay.

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with a Hat” (1905)

From “Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso: The Steins Collect” docent Caty:

Many paintings pushed the boundaries of art at the 1905 Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris, but even in a gallery full of canvases dubbed “fauves” (wild beasts), Matisse’s Woman with a Hat stood out. Peeking out from beneath a wildly improbable hat is Matisse’s wife, Amélie. Her face is built from splotches of green, yellow, pink, coral, colors that seemed completely arbitrary to those first astounded viewers in 1905. Madame Matisse is also surrounded by those same colors, in forms scraped haphazardly onto the canvas. This background does not evoke either a domestic setting or an outside one; it doesn’t even present a space at all. It’s just paint on canvas, a vivid arrangement of color and texture.

Although viewers in 1905 had seen abstract backgrounds in portraits before (in van Gogh, for example), their inventive forms and colors were read as signs of the intense emotions of the depicted personalities. With Matisse’s portrait, however, viewers saw that the wildly expressive dashes of color did not actually create an expressive face, since Madame Matisse is absolutely calm, almost detached. Leo Stein described this portrait as “the nastiest smear of paint I have ever seen.” So, naturally, a few days later he and his sister Gertrude went back to the Salon and bought it, embarking on a decade of unprecedentedly brave art collecting. In the Grand Palais exhibition, we get to follow this painting to its first, new home in the Stein’s Paris apartment, where it kept company with other icons of modern art. In a 1907 photo of Leo and Gertude’s salon, Picasso’s equally revolutionary but vastly different Portrait of Gertrude Stein threatens to crush Madame Matisse’s hat. The higher canvas, with its ponderous monumentality and earth-toned palette, emphasizes the lightness of Matisse’s conception and the liberty and joy in his handling of paint. These two works even now represent the two poles of experimentation in avant-garde art at this chaotic time. It comes as more of a surprise to see Woman with a Hat paired with another portrait (at the right edge of the photo) by the Impressionist Renoir, who is not an artist we expect today to see displayed on the same wall as these young revolutionaries. However, these two paintings get along very well, and their juxtaposition highlights the fact that, for all of the incomprehension most people experienced when looking at Matisse’s art, he was not simply breaking with the traditions of portraiture but also playing and harmonizing with them.

Although viewers in 1905 had seen abstract backgrounds in portraits before (in van Gogh, for example), their inventive forms and colors were read as signs of the intense emotions of the depicted personalities. With Matisse’s portrait, however, viewers saw that the wildly expressive dashes of color did not actually create an expressive face, since Madame Matisse is absolutely calm, almost detached. Leo Stein described this portrait as “the nastiest smear of paint I have ever seen.” So, naturally, a few days later he and his sister Gertrude went back to the Salon and bought it, embarking on a decade of unprecedentedly brave art collecting. In the Grand Palais exhibition, we get to follow this painting to its first, new home in the Stein’s Paris apartment, where it kept company with other icons of modern art. In a 1907 photo of Leo and Gertude’s salon, Picasso’s equally revolutionary but vastly different Portrait of Gertrude Stein threatens to crush Madame Matisse’s hat. The higher canvas, with its ponderous monumentality and earth-toned palette, emphasizes the lightness of Matisse’s conception and the liberty and joy in his handling of paint. These two works even now represent the two poles of experimentation in avant-garde art at this chaotic time. It comes as more of a surprise to see Woman with a Hat paired with another portrait (at the right edge of the photo) by the Impressionist Renoir, who is not an artist we expect today to see displayed on the same wall as these young revolutionaries. However, these two paintings get along very well, and their juxtaposition highlights the fact that, for all of the incomprehension most people experienced when looking at Matisse’s art, he was not simply breaking with the traditions of portraiture but also playing and harmonizing with them.

Edouard Manet’s Woman Reading (1879-80)

From “Manet at the Musée d’Orsay” docent Caty:

For a woman, being alone in a public establishment in 1870s Paris would be considered a little risqué. However, the figure in Edouard Manet’s Woman Reading—dressed in her forbidding armor of frilly fashion—seems blithely indifferent to this possibility. She is intensely focused on her reading, instead of the people around her. Manet focuses us very closely on the reader herself. We don’t see much of her surroundings, and two small details alone —the wooden rod attached to her illustrated journal and the glass of beer on the table beside her —let us know that she is not in a private garden, but in a public café. For many of Manet’s contemporaries, painting a picture of a woman in public would have been an opportunity to put her on display, while perhaps making a statement about the moral dangers for women in the modern city. Here, Manet does nothing of the sort. Manet’s early work, like his notorious Olympia or his cryptic Luncheon on the Grass (both at the Musée d’Orsay) earned him his reputation for provocation. In his later career, however, Manet became less openly confrontational, and more exploratory and loose in his painting technique. This is in part due to his close friendships with many Impressionist artists: Monet, Degas, and especially Berthe Morisot, who was in some ways the most experimental painter in the whole circle. We see her influence on Manet in Woman Reading, in the fast, open brushstrokes and softness of its forms. Also, Morisot’s own swiftly-done, sensitive studies of single female figures may have influenced Manet’s brisk, gently humorous depiction of a woman navigating the modern world. But a bit of the old mischievous, confounding Manet does remain here and in much of his late work: is this woman sitting in front of a window onto a garden, or is that a painting of a garden? He composes and crops the picture in just such a way that we can never be completely sure…

Claude Monet’s Cliff at Dieppe (1882)

From “Monet at the Grand Palais” docent Katie: Cliff at Dieppe (1882)

is one of several works Monet painted during an extended stay in Normandy. This area of France was meaningful to him for many reasons. Having grown up in the port city of Le Havre, the nearby Normandy landscape was also where Monet began to hone his painterly craft as a young artist, working alongside his teachers, Johan Jongkind and Eugene Boudin. The dramatic rocky cliffs, high winds and churning sea presented him with natural opportunities to challenge artistic tradition, and to develop an innovative vocabulary to represent his subjective experience of a constantly changing site. In Monet’s lifetime, the Normandy coast transformed from a series of sleepy seaside villages into a bustling resort destination for wealthy Parisians. With the arrival of the railroad linking Paris to Normandy in the late 1840s, tourism in the area exploded. These recent developments are evident in Monet’s painting, with its house—likely a new construction—perched on top of the cliff, and its bathing tourists down on the beach below, depicted as tiny blue specks of paint. These small markers of human presence contrast with the striking grandeur of the natural landscape. The wildness of the white, chalky cliff is emphasized through swift, vertical strokes of paint. Monet’s composition focuses our attention on the drama of the cliff’s sudden drop-off to the beach below. On the other side of that cliff, rocky forms give way to tousled, green vegetation. Here, Monet mixes multi-directional strokes of paint to create the impression of a swirling, wind-blown hillside. To play up the startling differences between the two kinds of landscapes within the painting, Monet includes a fence which separates the cultivated land—with other, small figures and vacation homes—from the wild, untouched part. His painting plays on a very real (and still very relevant) tension between safe landscape, domesticated for visitors, and a dangerous one, highlighted through a frenzied drama of paint applied to a canvas.

Eiffel’s “72”

From “Understanding Eiffel” docent Dennis:

Everywhere on the facades of the Palais du Louvre, you’ll see authoritative initials belonging to French rulers who reigned from inside its sumptuous interiors. At the Eiffel Tower, however, a more modern story emerges through its inscriptions. At the level of the first platform, just above the cross-braced latticework where the curved legs come together, 72 names wrap around the entire tower. And not one of them is Louis, Charles, or Napoleon! These names—embossed into iron rather than stone—belong to the great men of modern French engineering, mathematics, and science. This fact alone tells us quite a bit about what the tower was designed to represent. Constructed exactly 100 years after the French Revolution, the tower was conceived as a symbol of Republican France, where science and savoir faire were celebrated over nobility and aristocracy. Some of the men listed here were born noble, and some were not. Nevertheless, they are listed side by side for their achievements , irrespective of birth or social position. In a 19th century Europe still dominated by royal dynasties, to commemorate meritocracy was a fairly radical idea. The spirit of these 72 names mirrors the story of the tower’s creator, Gustave Eiffel, a self-made man of humble birth. There are a few household names among the 72: Antoine Lavoisier, considered to be the father of modern chemistry for developing the periodic table and metric system; André-Marie Ampère, the mathematician and physicist who measured electric current (the Amp is named after him); and Léon Foucault, who proved the rotation of the earth through his famed “Foucault’s Pendulum” at the Panthéon. There are also names that most people would not recognize: the inventor of margarine, the scientist who discovered the greenhouse effect, the designer of Paris’ sewer system. A name you will not find among Eiffel’s 72 is Sophie Germain, whose work on the theory of elasticity was crucial to Eiffel’s calculations for the tower’s construction. Her biographer argues that Germain was not included on the tower because she was female. So, while in many ways the Eiffel tower was a symbol of modernity, it also represented a late 19th-century society that still had progress to make.

, irrespective of birth or social position. In a 19th century Europe still dominated by royal dynasties, to commemorate meritocracy was a fairly radical idea. The spirit of these 72 names mirrors the story of the tower’s creator, Gustave Eiffel, a self-made man of humble birth. There are a few household names among the 72: Antoine Lavoisier, considered to be the father of modern chemistry for developing the periodic table and metric system; André-Marie Ampère, the mathematician and physicist who measured electric current (the Amp is named after him); and Léon Foucault, who proved the rotation of the earth through his famed “Foucault’s Pendulum” at the Panthéon. There are also names that most people would not recognize: the inventor of margarine, the scientist who discovered the greenhouse effect, the designer of Paris’ sewer system. A name you will not find among Eiffel’s 72 is Sophie Germain, whose work on the theory of elasticity was crucial to Eiffel’s calculations for the tower’s construction. Her biographer argues that Germain was not included on the tower because she was female. So, while in many ways the Eiffel tower was a symbol of modernity, it also represented a late 19th-century society that still had progress to make.

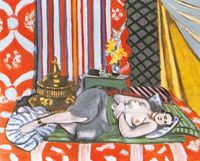

The Dazzle of Matisse

From our “Monet and More” Orangerie docent Kristen:

From our “Monet and More” Orangerie docent Kristen:

Matisse’s paintings often depict subjects, like the reclining woman at the center of this painting, which fool you into thinking his art is all about relaxation. His sensually posed model may be taking a breather here, but our eye sure gets a work out. It has to shuttle back and forth to take in all those marvelously complex decorative structures. One Matisse writer described this effect as “optical dazzle,” as if a flash bulb has gone off in our eyes. Notice how the simple, boldly striped pattern of the North African blanket competes with the French-style red wallpaper surrounding it. Matisse was an avid collector of fabrics from around the world, and adorned his studios in Nice with them. His fascination with textile design was related in part to where he grew up, in Bohain, in northern France, a region dominated by the textile industry. Other influences came from further afield. This painting also reflects Matisse’s travel experiences outside of France, specifically in North Africa. Throughout the 1920s, Matisse did a whole series of odalisque fantasy paintings, featuring his favorite model Henriette playing the role of a kept woman in a harem. This painting, for example, is only one of four odalisques paintings in the Orangerie’s collection alone. While at the Orangerie, be sure to take a look at Picasso’s Woman with a Tambourine (1925) which hangs nearby. It is a deliberate, slyly provocative response to Picasso’s rival Matisse, and his fascination with this voluptuous subject.

Read more about our Orangerie tour

Mystery Doors on the Seine

From our “Historic Heart” walking tour docent Larissa:

Have you ever noticed those mysterious numbered doorways—like the one at the left in our photograph above—while you were strolling along the Seine? Have you ever wondered where they might lead? Some of these doors, now blocked up, used to connect the river with the houses built along its banks. Others led to shops built into these embankment walls themselves. Just in the shadow of Notre-Dame cathedral, there was a door leading directly into the city’s oldest hospital, Hôtel-Dieu. (You can see the chimneys of today’s Hôtel-Dieu jutting just above the wall in our photograph). 17th-century crowding at the hospital (by then already over 900 years old) led to an unusual idea for expansion. Additional hospital wards were built over a nearby bridge, the Pont au Double! The nuns who worked at the hospital used passageways to go directly from the wards down to the river. Every day they emerged from these doorways to wash their patients’ clothes in the less than clean river water, earning them the nickname les petites laveuses or “the little washerwomen.”

Read more about our “Historic Heart of Paris” walking tour.

Renaissance Gem

From our “Hidden Masterpieces of the Louvre” docent Amy:

One of the most beautiful Renaissance paintings in the Louvre— Jan van Eyck’s Chancellor Rolin Madonna c. 1434— is also the most difficult to find. You won’t find it in the more crowded Italian galleries, where everyone is heading to see the Mona Lisa. It’s in the Netherlandish rooms (Richelieu second floor, galleries 4 and 5), where a whole other equally fascinating Northern Renaissance unfolds.  Look at how van Eyck’s painting balances scrupulous attention to earthly details with spiritual symbolism. In the walled garden in the background, for example (itself a symbol of Mary’s virginity), the minutely-detailed white lilies symbolize her purity; the red roses, the Passion of Christ. The two birds (magpies) on the garden’s path allude to death. In this one tiny devotional image then, we have both a meditation on the awesome powers of the divine and on the human ability to make sense of its creation.

Look at how van Eyck’s painting balances scrupulous attention to earthly details with spiritual symbolism. In the walled garden in the background, for example (itself a symbol of Mary’s virginity), the minutely-detailed white lilies symbolize her purity; the red roses, the Passion of Christ. The two birds (magpies) on the garden’s path allude to death. In this one tiny devotional image then, we have both a meditation on the awesome powers of the divine and on the human ability to make sense of its creation.

Read more about our “Hidden Masterpieces” tour at the Louvre.