The Paris Muse team recently enjoyed an inside peek at the exhibition The Origins of Greece: Between Dream and Archaeology with our educator Claudia Eicher.

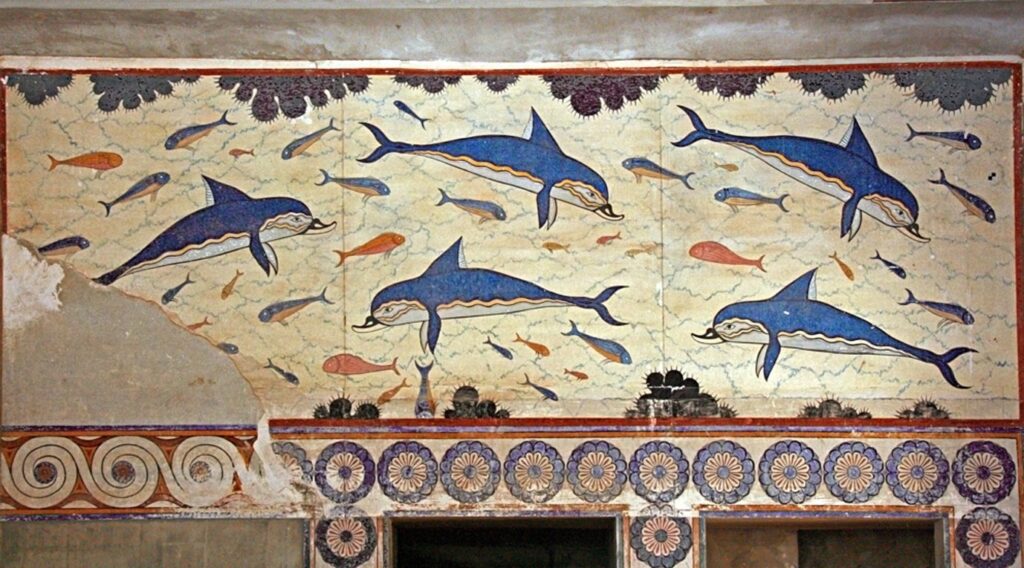

Claudia Eicher (above) is a Muse educator, archaeologist and freelance curator. Above right: “Prince of the Lilies” fresco from the Minoan palace of Knossos, Crete, (1700-1450 BCE). Reconstruction at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

As part of her studies at the Ecole du Louvre, Claudia served on the curatorial team and and designed a family program at the National Museum of Archaeology just outside of Paris. The exhibition displays art and material culture from the Greek Bronze Age (3000 – 1050 BCE) through the excavations and fanciful reconstructions of various sites between 1870 and 1939.

Claudia offered us insight into a number of interesting developments in the field of archaeology in the late 19th century, one example being the early interpretations of Cycladic sculptures, which were originally thought to be idols related to cult or ritual. More recent studies have focused on the possibility that these figures were painted, providing us with deeper information concerning their use. We were also fascinated to see some of the objects and texts from Heinrich Schliemann’s legendary quest to link the heroes of Homeric epic to material culture excavated at Troy and Mycenae.

For me, one of the highlights of the exhibition were the fragmentary wall paintings from the Cretan Palace of Knossos, creatively reconstructed by the artist and archaeological draftsman, Emile Gilliéron, and his son of the same name. These paintings decorated staterooms, living quarters and entrances at the 1380 – 1100 BCE palace, and reveal an intimate knowledge and interest in the natural world, from sea life to magical blue monkeys in fields of saffron.

Some of the Classical works on our Introduction to the Treasures of the Louvre tour, a metope from the Parthenon, for example, were restored in the 19th century, and the museum has since decided to remove those restorations. I will now look at these works in a new light. I will try to imagine not only how these works appeared when they were made, but also how they have been reconstructed in the minds of the people who engaged with them since that point to the present day. Modern archaeologists have criticized the Gilliéron restorations, and understandably so. As an archaeologist myself, I was taught to record data as empirically as possible, and not to apply tentative interpretations to the reconstruction of finds. However, the exhibition left me with such a powerful impression of creative energy that it leads me to question how severe we should be on the father and son team. If the archaeologist and writer, Jacquetta Hawkes, is right and “every generation gets the Stonehenge it deserves,” then not only is the practice of historical disciplines tied to the present, indeed it cannot exist without the specific interests of the present. Historical and artistic interpretations, however sound, are inherently subjective. Why not, then, leave room for creative expression?

This exhibition has been extended until February 2, 2015.