Some fathers sire children. Others “give birth” to cultural movements.

This Father’s Day we celebrate five French artists who changed the course of art history.

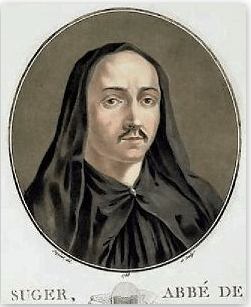

Abbot Suger (1081-1151): Father of Gothic Architecture

The world-famous Gothic style began with an ambitious abbot who dreamt of replacing dank, dark churches with light-filled spaces reaching up to heaven. Abbot Suger, who lived at the St. Denis abbey in the north of Paris, is credited what would come to be known as the Gothic style. At the time, however, it was simply called opus francigenum, or “the French style.” The hallmarks of this quintessentially French architecture is pointed arches, soaring vaults, and vast windows with a kaleidoscope of color. Notre Dame cathedral in Paris is one of the earliest examples of this cutting-edge style that forever changed the face of sacred architecture.

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863): Father of French Romanticism

Hardly restricted to painting, Romanticism is a literary, musical and artistic movement characterized by a focus on the individual, the subjective, and the weirdly fantastical. In direct opposition to Neoclassicism, which preached a strict adherence to formal rules and well-established tradition, Romanticism celebrates the imagination and unbridled nature as gateways to transcendence and truth. Despite its name, it has nothing to do with what we would call “romantic” love. In fact, the term derives from the medieval “romance,” or tale of chivalric adventure, with its emphasis on human emotion and all things strange. Delacroix’s novel use of color, bold brushstroke and exotic subjects are all hallmarks of the movement, launched by his Death of Sardanapalas (1827) at the Louvre, home to many of his most ambitious paintings today. You can also learn more about his work at the Musée Delacroix in Paris.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877): Father of Realism

Just as Delacroix rebelled against Neoclassicism, Courbet (pictured above in his famously frenzied self-portrait, The Desperate Man, 1843-45) in turn waged war against Romanticism. Rather than featuring the far-off and the exotic, he turned his painterly eye to the everyday. “I’ve never seen an angel,” he said, “so how can I paint one?” Wielding paintbrushes and canvases, Courbet led an unabashed assault on the prevailing conventions of the art world, and was harshly criticized – and indeed rejected – by the establishment. He depicted peasants and portly clerics rather than svelte aristocrats or the idealized heroes and heroines of literature. He famously painted a small town burial in his hometown of Ornans, depicting the locals with the dignity and respect normally given to classical heroes. As radical in real life as in his art, he participated in violent popular uprisings, served a brief prison term, and was exiled to Switzerland. The Orsay museum boasts many of his works.

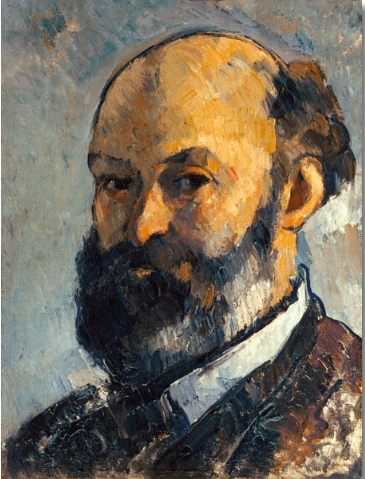

Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906): Father of Modern Art

Paul Cézanne allegedly once said, “I want to astonish Paris with an apple.” Take a look at his many still-lifes and you’ll see what he meant. Cézanne’s apples seem to tumble off slanted tabletops strewn with carelessly crumpled napkins and impossibly hovering glasses and cutlery. These “errors” are in fact the artist’s efforts to dismantle one-point perspective, which had dominated art since the Renaissance. After all, we move around things – literally and figuratively – to reach understanding, so why not depict multiple points of view? Misunderstood in own lifetime, he happens to be considered the father of many artistic movements of the 20th century, including Cubism and abstract art. The ultimate praise came from Picasso and Matisse, who both said of Cézanne, “he is father to us all.” Explore Cézanne with us on our Age of the Impressionists at the Orsay tour.

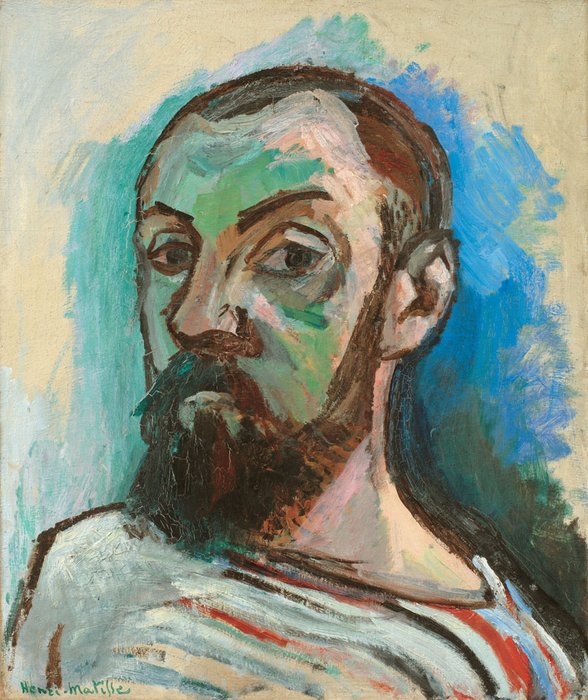

Henri Matisse (1869-1954): Father of Fauvism

Throughout his long career as an artist, Henri Matisse pushed his painting into new territories. But his first flirtation with the avant-garde was jumpstarting the Fauvist movement. In 1905 he exhibited with a group of artists who were experimenting with riotous color and spontaneous brushstroke. One critic called the gallery exhibiting their intentionally unsophisticated works a cage of wild “beasts,” fauves in French. The term “fauvism” was born, with Matisse its undisputed leader. You can learn more about Matisse on our Masterpieces of Modern Art at the Pompidou Center tour. Matisse remained artistically active until his last days, experimenting not only with painting but sculpture, printmaking and paper cut-outs.

Bonne fête des pères!